Poland Part II Day 7.1

My grandfather wanted to take me to Bunk 15, the barracks where he slept for most of his nights as a prisoner of Auschwitz. The barracks still stand. We might have gone off by ourselves, but a Dutch filmmaker who was attending the conference approached my grandfather to participate in an interview for his documentary. The man wanted to film my grandfather walking around the Birkenau death camp. They would film me, too, walking with him; a grandfather pointing out his memories to his grandson. So we struck a deal. If they could arrange for a car and could get us in to the locked and roped-off barracks, we would do it. They liked the idea of filming inside the barracks. They could get someone from the museum to unlock the gates to drive us in to the restricted section. They could open the doors of Bunk 15. Sure.

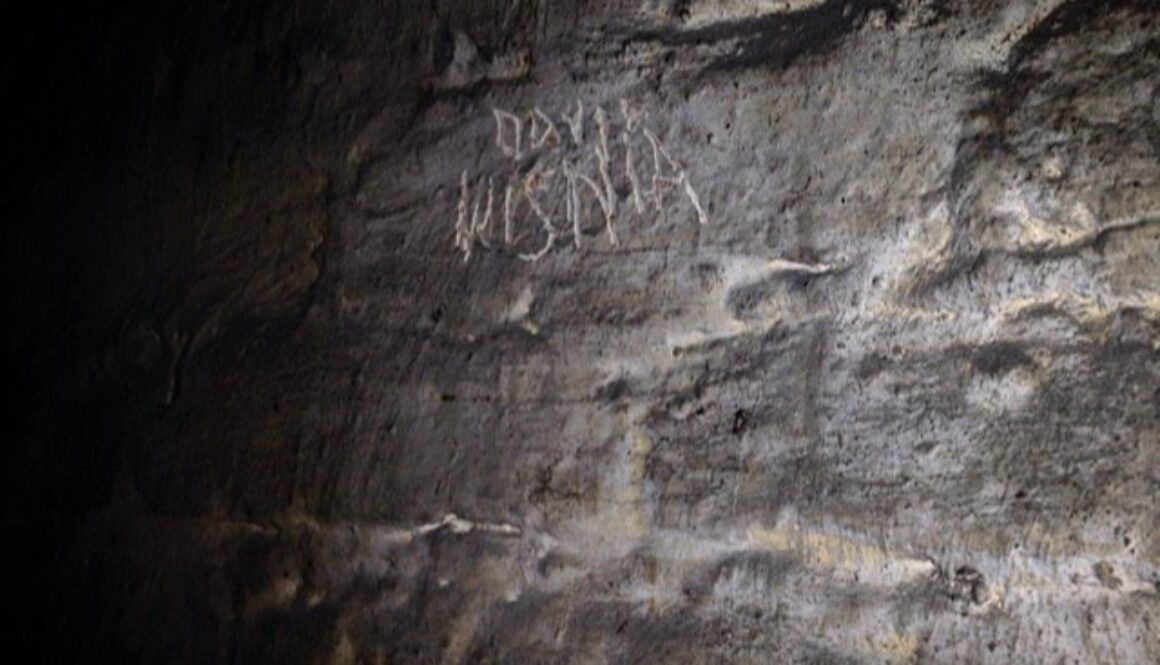

My grandfather chiseled his name into the wall in the spot where he used to sleep as a prisoner of Auschwitz, in Barracks 15. This was years ago, when he returned after the war, it’s hard to remember when. But it has been there for decades. Many people have seen it, he points it out to people when he goes back. This was his buksa, his bed. No pillow or mattress. Just wood. He shared it with three other strangers; one thin, threadbare blanket to share between them. You could not stand up, you had to slide in. A bookshelf for people. You were lucky if you survived through the night, but you would wake only to find yourself still in this place.

There were many years my grandfather did not talk about his time here. David’s oldest son, my father, didn’t find out his own father was a Holocaust survivor until he was 16. My father had only discovered that David was born outside the United States a few years earlier. But now, my grandfather will tell you about it. He will come back to Auschwitz and show you. He has written it on the wall. He wants the world to know he was here.

“Ok, now we’re going to have you just walk down and around in between the bunks in silence, and we’ll follow you with the cameras.”

Even in daylight, Building 15 was dark. The stone walls and the wooden shelves which were used as beds were packed in tightly, cutting off most of the light. The windows seemed irrelevant. I followed my grandfather down one aisle and around the other, the documentary crew following behind us. There was not much room to move around. It was hard to picture 100 men in this space. It was cold. It was appalling. My grandfather slept here?

“Ok, now we’d like you to ask your grandfather some questions.”

They wanted me to prompt him from off camera. What did it smell like? What did it sound like? For all the detailed documents and records that were kept, none will really tell you what it was like to be a prisoner in Auschwitz. Nothing can, except the prisoners themselves.

The barracks were kept clean. Even though there was nothing but mud outside, you had to keep the barracks clean because they would be inspected by the Nazi guard. The Germans were afraid of disease spreading.

What was the mood like among the prisoners? Was there ever laughing? Not really. When you got food, when you had something to eat, there was a good mood. If you managed to get a bit extra, that was a great moment. There were occasional moments of sharing. But if you stole someone’s bread, the other prisoners would beat you to death. Prisoners would turn on each other all the time, like animals. You had to look out for yourself, that’s how you lived. Your survival depended on the death of someone else.

“Ok, now can you say that again, but over here by the door, in the light.”

There are only so many questions you can ask at once, theres only so far you can press. You can’t force someone to go back to a place they don’t want to go, even if they are already there. You’ll break them. It was already difficult being in the barracks, and the cameras made everything more complicated. It was beginning to feel like a conversation I wasn’t really involved in, even though I was.

They finished the interview with my grandfather outside the entrance to the barracks. I heard them laughing. My grandfather had lightened the mood, he always does. I stayed inside the bunk and walked around by myself, without the cameras behind me. I stood in the center taking everything in. I stood there for a while. Then I took out my own camera and took a picture.

Everything here is complicated. Nothing is appropriate.

My grandfather called back to me.

“Avi, ok, let’s go. Get out of that hell hole.”

Don’t mind if i do.